Emotet Illuminated: Mapping a Tiered Botnet Using Global Network Forensics

Over the past several years, Emotet has established itself as a pervasive and continually evolving threat, morphing from a prominent banking trojan to a modular spam and malware-as-a-service botnet with global distribution. After emerging in June 2014 targeting German and Austrian customers, Emotet demonstrated new capabilities in 2015 as it expanded its scope to banking customers in Switzerland [1]. Since that time it has acquired new capabilities, adding modules such as credential stealing, networking spreading, email harvesting and address book stealing, among others [2] [3] [4].

Emotet’s modular nature has allowed the botnet to adopt various propagation methods; its power to avoid detection has only increased over time while its operators have shifted their focus to offering the botnet as a service to other bad actors. In its current form, Emotet typically spreads via malicious links or attachments in phishing emails sent from infected devices. Recent reports suggest that Emotet is responsible for about 60% of all spam containing malicious payloads [5]. While Emotet phishing campaigns have only been observed delivering Emotet itself, once a computer is infected with Emotet, it can then be used to drop additional malware families. Emotet’s malware distribution infrastructure is complex, utilizing a plethora of compromised hosts for hosting malware and several tiers of hosts controlling the distribution infrastructure.

Emotet’s command and control (C2) infrastructure is equally complex. The actors maintain over a hundred different C2s at any given time, frequently updating which C2s are active throughout the day. As will be discussed throughout this blog, the C2 infrastructure is tiered in several ways, making their infrastructure notably resilient to individual C2 disruptions.

Several researchers, cited throughout this blog, have discussed Emotet’s C2 infrastructure from a malware analysis perspective. By pairing this approach with network-based visibility and analysis, we are able to share important insights about the shifting nature of this pervasive threat and better protect the global internet.

Our Approach

CenturyLink’s Black Lotus Labs has been tracking Emotet’s C2 infrastructure since late 2017. Many organizations currently tracking Emotet monitor incoming spam emails and obtain Emotet’s main payload via the malicious URLs included. From there, C2s can be extracted from memory when running the binary in a sandboxed environment. Black Lotus Labs enhances this approach by also observing the traffic patterns of the botnet itself.

Using a seed of previously identified C2s, we employ Netflow-based heuristics to identify bots communicating with C2 infrastructure. For example, if an IP address frequently communicates with a C2 on its C2 port, there is some confidence that this IP address is a bot. Over the past six months, we have, on average, identified 40,000 unique Emotet bots daily. Figure 1 shows our daily bot count for 2019 to date. The large uptick in mid-March aligns with the emergence of Emotet samples using new communication protocols.

With several labeled C2s and a pool of known bots identified our goal is to proactively identify new C2s utilizing our network visibility. To do this, we train a machine learning classifier to identify new C2s going forward. Since bots talk to many popular hosts as well as C2s, we do not inherently trust the output of the machine learning classifier alone. In order to validate an Emotet C2, we emulate the protocol and ensure that an IP address responds in the proper fashion.

Using the above approach, throughout 2018 we were able to identify previously unknown C2s an average of seven days before popular publicly available trackers. Since Emotet’s C2 list is hard coded in the binary and their infrastructure changes rapidly, the code and C2 list running on an infected device must be frequently updated. As bots change to new C2s, our algorithms can see this change and identify new C2s, sometimes before they are even distributed in a new binary via spam campaigns.

Bots as C2s

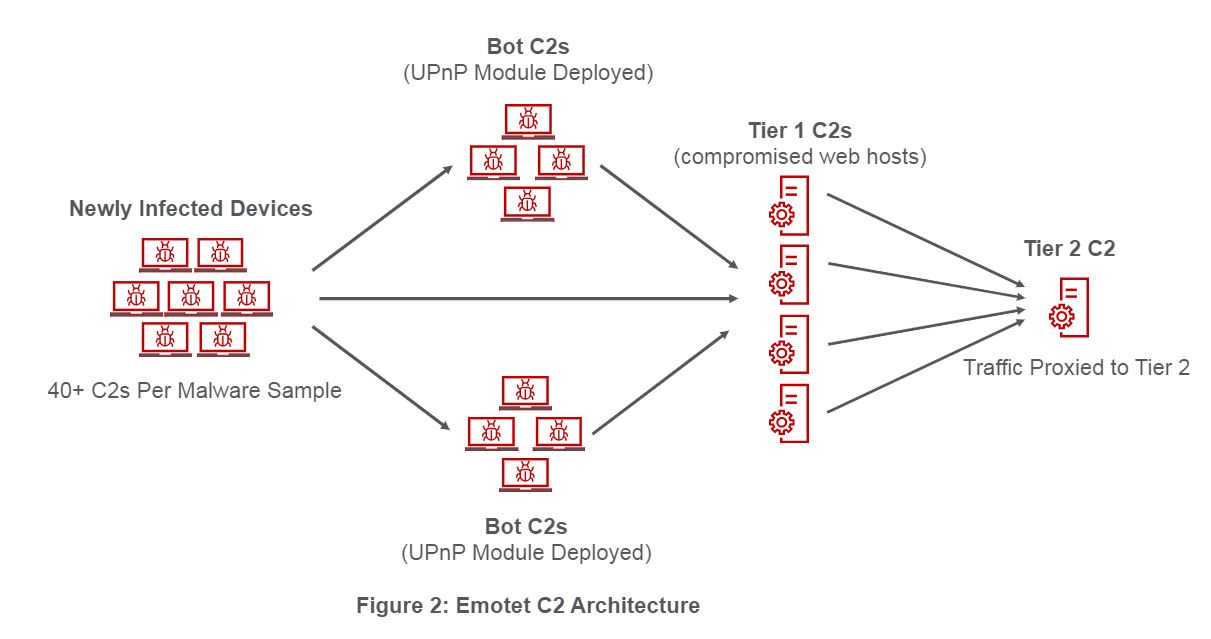

In April 2019, reports began surfacing that Emotet was potentially using IoT devices as C2 infrastructure [6]. Several security researchers tracking Emotet quickly disclosed these were actually infected Windows devices acting as C2s [7] [8]. During certain infections, Emotet deploys a UPnP module, which allows an infected device to act as a C2. In order to effectively use the infected device as a C2 server, it needs to be exposed to the internet and accessible to bots. Most of these infected devices are behind a router providing network address translation, and therefore not allowing inbound connections to the infected host. The UPnP module opens a port on the user’s router which then forwards inbound connections to a port on the infected device managed by the Emotet module. These “Bot C2s” do not handle actual C2 communication, but instead, act as a proxy by forwarding the communication on to a Tier 1 C2. In contrast to the Bot C2s, Tier 1 C2s are typically compromised webhosts which also forward their C2 communication on to a Tier 2 server. Emotet’s main payload will typically have over 40 different C2s consisting of both Bot C2s and Tier 1 C2s. A simplified diagram of Emotet’s C2 infrastructure is shown in Figure 2. Going forward, we will consider Tier 1 C2s as the compromised web hosts and Bot C2s as infected devices with the UPnP module deployed.

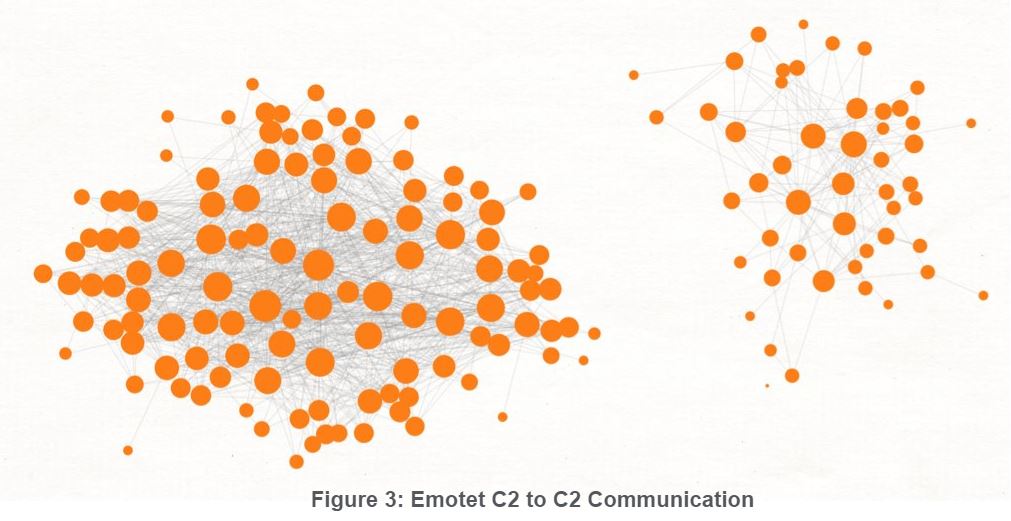

Black Lotus Labs has observed this behavior since mid-2018 based on network traffic alone, corresponding with the timeframe of other reports discussing the UPnP module for the first time [9] [10] [11]. This behavior was first identified when validated C2s started being labeled as “bots” by our bot-finding heuristics mentioned earlier, meaning validated C2s started speaking to other validated C2s on their C2 ports. When we plot the C2-to-C2 communication as a graph, you can see two distinct clusters of C2s as shown in Figure 3. This aligns with reports from other Emotet botnet researchers that have identified two separate infrastructures, typically referred to as Epoch 1 and Epoch 2 [12] [13]. Epoch 1 is currently the larger of the two botnets.

During the month of May 2019, our automated botnet tracking system identified and validated 310 unique C2 IP addresses. Within this same month, 208 of these C2s were also identified as bots via bot-finding heuristics. Analysis of these identified Bot C2s confirm the majority are hosted in dynamic broadband IP ranges. DNS records, as well as scanning history via services like Shodan, also confirm these IPs are internet service customers, not compromised webhosts. When looking at the other 102 C2s, we see that most of the IP owners are hosting providers typically used to host web services. Scanning history shows that most of these IPs are vulnerable webhosts matching the common criteria for Emotet Tier 1 C2s. This analysis reveals that within the last 30 days about two-thirds of Emotet’s active C2 infrastructure is comprised of infected devices (Bot C2s).

When looking at the amount of unique C2 IPs for 2019 so far, over 80% appear to be Bot C2s. This is most likely because Bot C2s change IP addresses much more frequently than the compromised webhosts. To check this assumption, the average number of days between first and last C2 validation was computed for both sets of C2s. For Tier 1 C2s the average was 38 days, while for Bot C2s this number was 17 days. It is important to note, this does not necessarily mean that C2 was always active for this number of days; however, it does represent the C2 was available for use at least twice during this period. Tier 1 C2s also appear to be active more frequently than Bot C2s, signifying that the compromised webhosts are online much more frequently than Bot C2s.

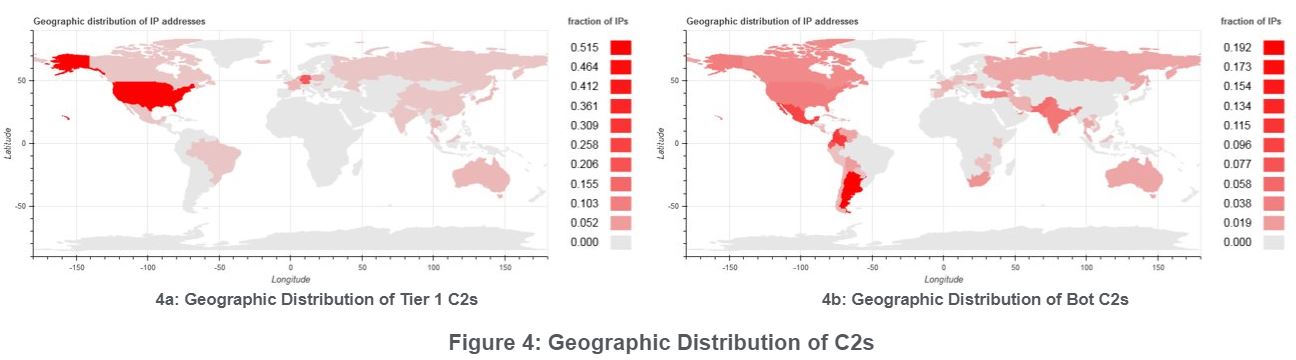

Figure 4 shows the geographic distribution of Tier 1 C2s vs Bot C2s. Tier 1 C2s are mostly dominated by IP addresses and hosting providers located in the United States and Germany. Bot C2s are mostly dominated by IP addresses and ISPs located in the Latin American region, including Argentina, Colombia, Mexico and Ecuador. There are also a handful of Bot C2s located in other countries such as Pakistan, India, United States, Turkey, Canada and South Africa.

Identifying Tier 2 C2s

The next step in enumerating Emotet’s C2 infrastructure is to identify Tier 2 C2s. Black Lotus Labs can identify Tier 2 C2s through correlations of network traffic alone. Previous approaches by other researchers for identifying Tier 2s required direct access to a Tier 1 C2 via the help of a hosting provider. Because the Tier 1 C2s proxy their traffic to a Tier 2 C2, and there is typically one Tier 2 C2 for each Epoch, by analyzing the commonality between the Tier 1 C2s and who they talk to, we can identify Tier 2 C2s. The current Tier 2 C2s as of May 2019 are 5.45.65[.]126:80 (Epoch 1) and 212.8.242[.]201:80 (Epoch 2). Each Tier 2 C2 only communicates with Tier 1 C2s from the same Epoch, showing the continued isolation between the two Epochs.

It is important to note that though we may not observe all the traffic to the Tier 2 C2s, we do observe traffic patterns from Tier 1 C2s that cross our network. Based on our visibility over the last 30 days, 14 IPs communicated with 5.45.65[.]126 on port 80/TCP, 13 of which were validated Tier 1 C2s. Traffic observed to 212.8.242[.]201 was similar, with 23 IPs communicating on port 80/TCP, 22 of which were validated Tier 1 C2s.

Malware Distribution as a Service

Though still sometimes discussed as a banking trojan, over the past several years Emotet has mainly been used as a malware distribution service for other families and it has become central to the eCrime ecosystem [14]. Emotet has been known to deploy other malware families such as Trickbot, IcedID, QakBot, Gookit, Dridex and others [14] [15] [3]. Using the bot heuristics described previously, Emotet infections can be correlated with the other malware families based on infected bot C2 communications. For example, based on our visibility over the last 30 days, we found that more than 17,000 unique bot IP addresses associated with Emotet C2s were also associated with Trickbot C2s. Trickbot is one of the most common malware families dropped by Emotet, aligning closely with what is observed from a network perspective. Our second highest correlated families — in the several thousands — are Emotet and Azorult. Emotet has also been known in the past to drop IcedID which, in turn, drops Azorult [16]. Similarly, we see about a hundred bots also associated with Danabot. Danabot’s C2 infrastructure was known to use the same IP address as Gookit at one time, which has also been dropped by Emotet [17].

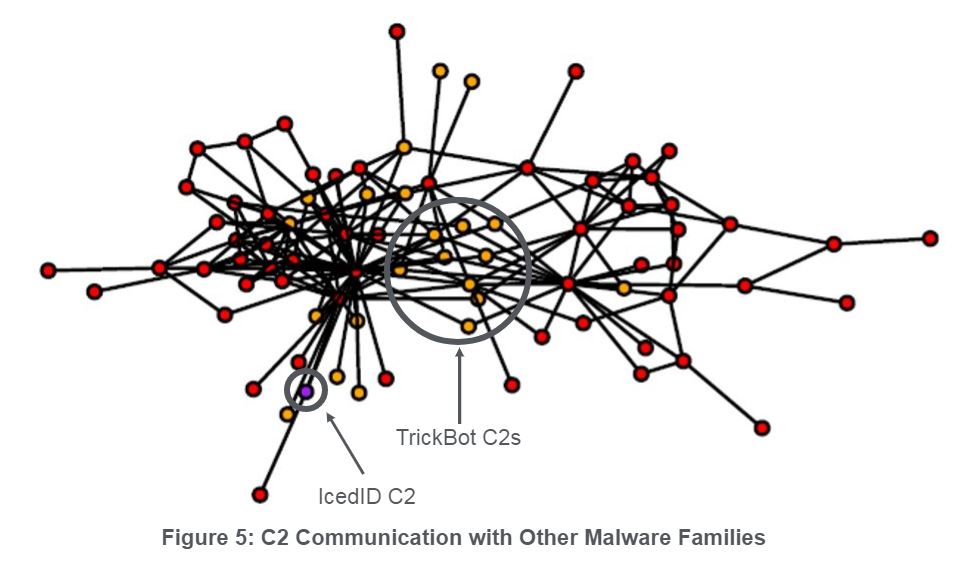

We also frequently observe our validated C2s communicating with other malware families as shown in Figure 5. At first, it was assumed that Emotet was using other malware family C2s to distribute its payloads, but we no longer believe this is the case. After being able to separate the validated C2 list between actual Tier 1 C2s and Bot C2s (as described above), it turns out that the actual Tier 1 C2s are not talking to any other malware families. This behavior appears to only exist with the Bot C2s. This may mean that the Emotet actors are dropping other malware family payloads on the same devices that they are using as C2s via the UPnP module. One would think that a botnet operator would want to keep the C2 infrastructure clear of other malware families, but this does not appear to be the case with Emotet. Of the 208 Bot C2s discussed earlier, 8% also appear to be also infected with Trickbot. One thought might be that Bot C2s are later used for other purposes, though we have validated an Emotet Bot C2 on the same day it communicated with a Trickbot C2 in the past.

Conclusion

Using automated botnet tracking, Emotet’s C2 infrastructure can be tracked via network visibility alone, independent of malware samples. Employing bot heuristics, Emotet’s C2 infrastructure can be separated into two lists: actual Tier 1 C2s that are compromised Linux webhosts and Bot C2s that are infected devices with the UPnP module deployed. Based on number of C2s, Emotet’s current infrastructure appears to be dominated by Bot C2s. By using the actual Tier 1 C2 list, the Tier 2 C2 for each Epoch can be identified. Bot heuristics can also predict which malware families Emotet is correlated with, helping track Emotet’s malware distribution as a service nature.

CenturyLink will continue leveraging our unique network visibility to help protect our customers and the internet at large by notifying other network operators of Emotet infected devices. Due to its rapidly changing and complex infrastructure, we continue to work with industry peers to keep up to date with this threat. We would like to thank Joseph Roosen (@JRoosen) for frequent discussions and collaborative work throughout this investigation. The Cryptolaemus group, as a whole [18], also deserves credit for continuously tracking Emotet and freely sharing information with the community. Researchers from ESET were also key partners in corroborating our findings related to the UPnP module. If you would like to collaborate on research similar to this, please contact us on twitter @BlackLotusLabs.

Read more Black Lotus Labs’ research.

References

| [1] | Center for Internet Security, “Emotet Changes TTPs and Arrives in United States,” [Online]. Available: https://www.cisecurity.org/blog/emotet-changes-ttp-and-arrives-in-united-states/ |

| [2] | CERT.PL, “Analysis of Emotet v4,” 25 May 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.cert.pl/en/news/single/analysis-of-emotet-v4/ |

| [3] | Proofpoint, “Threat Actor Profile: TA542, From Banker to Malware Distribution Service,” 15 May 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.proofpoint.com/us/threat-insight/post/threat-actor-profile-ta542-banker-malware-distribution-service |

| [4] | MS-ISAC, “MS-ISAC Security Primer- Emotet,” [Online]. Available: https://www.cisecurity.org/white-papers/ms-isac-security-primer-emotet/ |

| [5] | Proofpoint, “Quarterly Threat Report Q1 2019,” 28 05 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.proofpoint.com/sites/default/files/pfpt-us-tr-q119-quarterly-threat-report-0528.pdf |

| [6] | Trend Micro, “Emotet Adds New Evasion Technique,” 25 April 2019. [Online]. Available: https://blog.trendmicro.com/trendlabs-security-intelligence/emotet-adds-new-evasion-technique-and-uses-connected-devices-as-proxy-cc-servers/ |

| [7] | [Online]. Available: https://twitter.com/JRoosen/status/1123231941707358210 |

| [8] | [Online]. Available: https://twitter.com/GossiTheDog/status/1121790583108857859 |

| [9] | Fidelis Security, “Emotet Update,” 26 July 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.fidelissecurity.com/threatgeek/threat-intelligence/emotet-update-2/ |

| [10] | Check Point, “Emotet: The Tricky Trojan that ‘Git Clones’,” 24 July 2018. [Online]. Available: https://research.checkpoint.com/emotet-tricky-trojan-git-clones/ |

| [11] | Webroot, “2018 Threat Report Mid-Year Update,” 2018 |

| [12] | “Cryptolaemus Pastedump,” [Online]. Available: https://paste.cryptolaemus.com/ |

| [13] | Trend Micro, “Exploring Emotet: Examining Emotet’s Activities, Infrastructure,” 16 November 2018. [Online]. Available: https://blog.trendmicro.com/trendlabs-security-intelligence/exploring-emotet-examining-emotets-activities-infrastructure/ |

| [14] | Crowd Strike, “2019 Global Threat Report,” 2019. |

| [15] | Sophos, “Emotet’s goal: drop Dridex malware on as many endpoints as possible,” 10 August 2017. [Online]. Available: https://nakedsecurity.sophos.com/2017/08/10/watch-out-for-emotet-the-trojan-thats-nearly-a-worm/ |

| [16] | B. Duncan, “One Emotet infection leads to three follow-up malware infections,” 26 September 2018. [Online]. Available: https://isc.sans.edu/diary/One+Emotet+infection+leads+to+three+follow-up+malware+infections/24140 |

| [17] | ESET, “DanaBot evolves beyond banking Trojan with new spam-sending capability,” 6 December 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.welivesecurity.com/2018/12/06/danabot-evolves-beyond-banking-trojan-new-spam/ |

| [18] | Cryptolaemus Team. [Online]. Available: https://paste.cryptolaemus.com/about/ |

![]()